This Dead-End American Life

Side-hustles, self-help spirals, and the creator economy's fatal flaw.

I went on a roadtrip recently where I tried my hand at digital nomadism.

Parked along the rocky, New England shoreline, I’m staring at my laptop screen instead of the ocean beyond it where the sun is setting.

I want to love the creator economy, but things would be a lot easier if I could just hate it instead. That seems to be the case for a lot of people these days. We’ve been sold on the idea that it’s a shortcut to financial freedom… but is it? I keep hearing that new technology makes it easy to set up and maintain life as a solopreneur, and that just a bit of persistence will pay off big time…

But is all that really true?

The creator economy is the new “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” fallacy.

Isobel’s boiling water for mac-n-cheese. I’m sitting on the foam mattress in the bed of the truck, connecting to my phone’s wifi hotspot. Our coastal roadtrip means stopping into coffee shops or working remotely—in the truest sense of the word—to get stuff done.

Parts of it are idyllic, but it requires a ton of flexibility, patience, and emotional regulation. Managing yourself and your workload is challenging enough on a normal day, let alone when you’re living out of a Toyota Tacoma with your partner. So while typing away in the descending darkness, all I could think about was the crossover between solopreneurship and the self-help industry.

We Americans have long fetishized the corporate-ladder-climb, gritting our teeth and grumbling all the while. But the undercurrent of built-up resentment now resembles an overflowing river, yet we’re all still pretending creator side-hustles are some shiny alternative to the stagnant, corporate jobs everyone loves to hate.

The American dream has gone from climbing the ladder to avoiding it altogether.

A growing number of people are buying into this idea of “side-hustle security”. I’m one of them, or I used to be… still am? It’s complicated.

I’m hearing more and more people describe how they feel stuck with low pay and without upward mobility (which just means they’re worried about a lack of future earning potential). And rightfully so. While “dead-end job” used to carry a largely negative connotation, as if it were something to avoid at all costs, it’s since flipped in the post-COVID burnout factory we find ourselves in. The want for purpose and passion feels palpable—same with the expectation to be compensated like a human being for prioritizing it.

That dead-end job is a coveted thing, but for different reasons than before. Sure, health insurance is still the big one. But really, it’s about having a safety net hidden in plain sight. Most wouldn’t admit it to their boss outright, but that dead-end 9 to 5 job is a great way to keep getting paid while quietly building your life-raft.

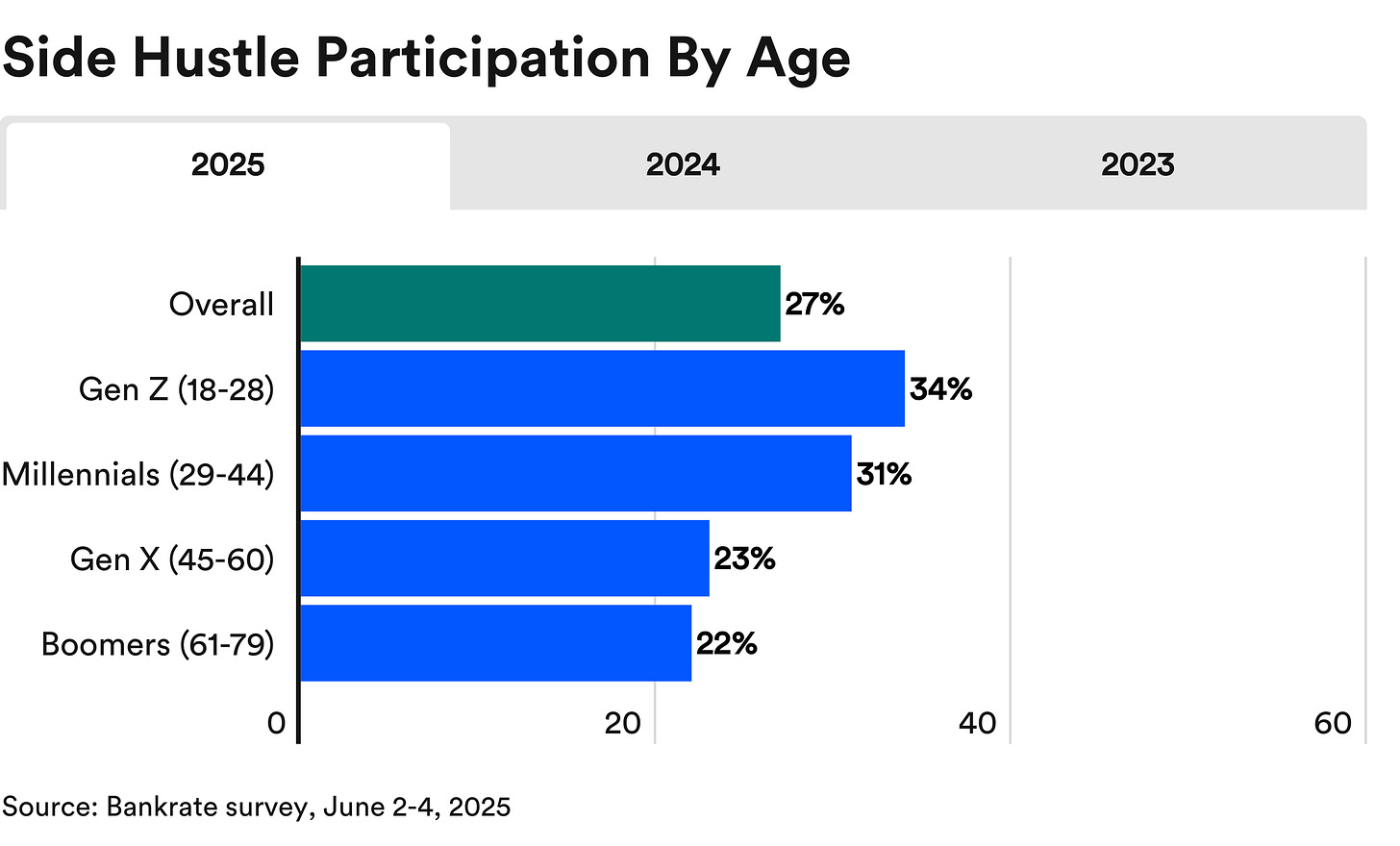

People are gambling their livelihoods, with plans to recoup once they get away from the rat race. Here’s a snapshot of folks who supplement their income with a side job:

34% of Gen Z.

31% of Millennials.

23% of Gen Xers.

22% of Boomers.

Wanting a better shot at success isn’t new, but modern-day snake oil looks different. So do the sales people.

Still, I’m seeing more and more examples of people hoping to be paid for their side-hustle, while scoffing at the idea of paying similar prices for art or services themselves. This shining contradiction seems to thrive in cultures where scarcity mindsets are encouraged. It emerges when people feel the need to compete for survival, and where someone else’s gain means your loss.

So people scrounge.

And, as Americans, we’ve been conditioned to believe that pulling ourselves up by our bootstraps works—that it’s the rule, not the exception. So, we sculpt our side-hustles with the expectation they lead us to a brand-new life. I’m not convinced.

This is the biggest problem facing the creator economy—and tech companies are exploiting it.

After dinner, I’m reconnecting to my phone’s hotspot to work on a few more things when I find myself scrolling. I catch myself quick enough, but I’m bummed. The same over-the-top, self-help guru sludge that repels me from using Instagram and Tiktok has found its way to Substack.

Great.

Everywhere, it seems, now has influencers who hawk themselves as proof of get-rich-quick schemes. More and more financial institutions are running ads with rags-to-riches stories, and tech startups keep glorifying side-hustles by cosplaying relatability: just look at the butcher, the baker, the candle-stick maker! But our self-inflicted, social media silos make it hard to see the reality of the bigger picture.

That’s why the self-help industry is thriving.

People want idealism and identity.

Carving out even the tiniest bit more cognitive bandwidth feels magical. Many of us are using that freed-up space to dabble in the creator economy; whether selling art, services, or something else entirely. I certainly am. We long for the sort of anti-capitalist utopia that would allow for full days of existing as curious humans instead of as competitive, corporate cogs.

I saw the perfect example of this while working from a coffee shop earlier on our trip. I’d been in line when the guy behind the counter got everyone’s attention without raising his voice. He didn’t do anything dramatic, and what he said wasn’t even all that outlandish, either.

He was the owner. And he was also taking orders, pouring drinks, and making small talk with customers. Handing a cortado to the person in front of me, he mentioned that this wasn’t the shop’s original location. Turns out, they’d started in a more popular area before uprooting and relocating to this rural spot.

“We chose somewhere with a slower pace and happier people” he said. “That’s worth more than the million we left on the table to do it.”

Damn.

Talk about helping yourself find health, wealth, and happiness. However you define it, this guy found a recipe that clearly works for him.

Self-help loves to promise growth, but operates like a Ponzi scheme… and so does the creator economy.

If it feels like tried-and-true multi-level marketing, that’s because it is. Except it’s app subscriptions instead of skincare products or Tupperware.

I dream of donating the contents of my bookcase just to be rid of the ruse. Because the whole thing feels like if Bernie Madoff rebranded, called himself Self-Made Madoff, and hit the podcast circuit to promote his proprietary method of selling your self-worth back to you.

Limited time offer, available whenever.

My own self-help story is rooted in a chaotic upbringing, all of which came to a head one night ten years ago. It’s 2015 and my back is against the wall of a dive-bar dance floor. I’m surrounded by friends. This is the kind of place where indie funk bands play, and where—if you closed your eyes—you’d see tapestry-covered, string-lit walls instead of tattered event promo posters.

People are engaged in a mix of start-n-stop conversations around me. Friends are bobbing and weaving between downbeats and drowned-out laughter.

I’ve never felt more alone.

I left just in time to have a panic attack on the floor of my own home that night instead of at the dive-bar. Then I drank and drugged my way to a few very dark places during a 10+ year journey through the ups and downs of a self-help growth spiral.

The self-help industry’s become a pipeline for creating autonomous, portfolio careers that fall apart.

This thing is broken and I’m really conflicted about it, because self-help saved my life, then gave me a new one.

It helped me get clear on my values, develop some self-efficacy, and start taking small steps toward a life I didn’t want to escape from. It helped me find my footing in the outdoor industry and again after a snowboard crash left me with a TBI and many months of recovery. Self-help systems even guided me through getting sober.

Books, podcasts, practices, and many, many, many sessions with therapists have helped me work on my shit. I’ve seen those principles translate to career success. I’ve wanted to believe, like many of us, that growing a side-hustle into a thriving creator business shouldn’t be all that different.

But, for that to be livable, it requires of you what a corporate role does… and then some. It may sound easy—you just do what you do at your job, but for yourself, right?

Not quite.

Fake it till you make it doesn’t really work, but we keep trying it anyway.

The gurus are encouraging the average Joes to be their own brand. Create an offer, build a product, get paid.

books

courses

communities

But self-help doesn’t teach digital fluency, it teaches dependency on self-help. So, while simultaneously promoting a culture of side-stepping small business support systems, I’m watching people stake their personal livelihoods on projects that traditionally require enterprise-level resources.

They don’t see it as a risk.

They should, but they don’t because they see themselves as the exception, not realizing the business acumen, software comprehension, and strategic execution required to generate something people will buy. And the people who won’t pay still want to tell you about their thing that’s for sale.

The dead-end isn’t the job or the side-hustle… it’s picking up self-help and never putting it down.

Another night of typing in the dark from the back of my Tacoma, and I’m suddenly, glaringly aware of the self-help loop I find myself in… the one I thought I’d escaped.

So now I can’t stop thinking about a memory from when I was 13. My family was on vacation at a lake house not far from where Isobel and I are camped for the evening. I’d just finished a computer science course to get a jump on things before starting high school that fall. Laptop in hand, I was sitting inside trying out some of the new HTML I’d learned for building websites. Later, we paddled to the middle of the lake with a canoe to camp out on an island. And so, the kernel of a dream planted itself in firmly my brain.

If only the rest were so simple.

In her description of artistic recovery, author of The Artist’s Way, Julia Cameron, describes “shadow artists” as the parts of ourselves we let get close to the thing we want but without actually getting it. This is self-help spiraling 101— thinking we can out-learn our way into being vulnerable enough to be brave. The sports agent who secretly wants to be an athlete? That’s a “shadow artist.” Same with the magazine editor who’d always dreamt of being a novelist. These are examples of getting close in proximity, but not in practice.

For me? This looked like becoming a marketing executive instead of becoming a writer—like working with software near sentences, and eventually writing sentences about software, but always from the shadows.

Fast forward and I’m 31. Laptop in hand, I’ve spent the week sitting outside while on a camping trip with my partner. I’ve just finished a summer of website configuration to get a jump on things before starting a project this fall. While on the road, I’ve been able to write, work on web projects with clients, and camp by the water.

So now, according to social media, it’s time I start writing fiction.

onward.

P.S. If you enjoy reading essays like this one, I also write a daily column. Sign up to get more field notes for navigating daily life.

I applaud your honesty and it's something I've felt before.

I've been both successful in brick & mortal (dance studio), entrepreneurship (SEO and lots of passive income) as well as corporate ladder (Engineering Manager).

I think the situation is incredibly nuanced. All have pros and cons, or better said, "good things" and "absolutely horrible things".

The offline studio was incredibly rewarding, but very tiring when you couldn't take a day off. Teaching class to 40 enthusiastic people is great... unless you have a fever or haven't slept because your kid was crying all night. Also, COVID absolutely shut down the business. It was tough for my partners.

The SEO stuff was incredibly passive but... super boring. And earning $2,000 a month stopped feeling good when one month I made $5,000 but never again.

The corporate ladder was in its truest sense a complete brainwash into the "we're family" idea. They raised me to Eng. Manager but didn't raise my salary or care much about me being a new dad. However, I loved just getting paid and some days I slacked off. I miss those days.

Same with remote or on-site. Working with two kids literally jumping on top of me isn't as good as they picture it.

My conclusion is that the idea of a "dream job" is just foolish. We have to be ready for a certain amount of grind.

I know a man that makes $100,000 over a weekend, many times per year, and yet sometimes he is very tired. Angry. Upset. I used to think I would never feel that way. But then I thought... Why shouldn't he be? I made $500/hour when some people make less than that per month, yet I hated the job.

Loved this Derek! Telling it like it is, through exceptional writing. Brilliant.